Against a New Orthodoxy: Decolonised “Objectivity” in the Cataloguing and Description of Artworks

Introduction

The value of the Paul Mellon Centre’s Photographic Archive is in its vast aggregated breadth: capturing images of artworks that might otherwise have been impossible to trace or compare in a time before Google searches and mass digitisation. Now digitised itself, it allows us to see something of the way cataloguing practice has encoded the attitudes and values of the times in which the archive was created.1 But more than re-presenting historical information, provenance, legacy titles, and description, digitisation can also serve to uncover the nature of our own recent intercessions into the records and descriptions of art and artefacts.

In the last few years there have been moves across galleries, libraries, archives, and museums (the GLAM sector) to address sensitive, outdated, colonial, and racist words in the description and interpretation of art and artefacts.2 As part of this much needed remediation, the Paul Mellon Centre (PMC) is undertaking an audit and making interventions within its own photographic archive records, identifying problematic historical language and titles, captured in the typed captions on the mount cards and now digitally disseminated online. In this article, we ask whether the act of changing words in records makes a significant impact in the ongoing, broader setting of deeply entrenched imperial and racist attitudes, practices, and behaviours in GLAM institutions and the collections they hold.

We are writing this piece in the final months of a two-year, AHRC-funded project which is itself part of the sector-wide effort to examine language use in cataloguing and interpretation practices. Entitled Provisional Semantics: Addressing the Challenges of Representing Multiple Perspectives Within an Evolving Digitised National Collection, the project focuses on how museums and heritage organisations can engage in decolonising practices to produce search terms, catalogue entries, and interpretations that can be fit for purpose in a future, evolving, digitised national collection.3 The project comprises a literature and practice review and three case studies that centre on collections held in Tate’s Library, the National Trust and the Imperial War Museums (IWM), and although some elements of the research are still in process, our learnings to date inform this article.

We suggest that although problematic words and terms undoubtedly need to be identified and addressed, there is no single, universally appropriate way of doing this, and that specificity of context, transparency of purpose, and research are crucial to making meaningful change in cataloguing. Further, we fear that the current impulse to revise object information texts (such as labels, online descriptions, or object records) using newly “decolonised” language is fundamentally reactionary and is increasingly becoming uncritically established as the “new objectivity”. That is, while the GLAM sector is ostensibly attempting to respond to the notion that “museums are not neutral”, we observe that efforts to rename, re-describe, and reinterpret cultural objects and artworks are often being made wholesale and in haste. The relatively obscure editing and cataloguing activities through which such changes are made has started to become a new site for planting and upholding the false sense of objectivity that cultural institutions have been so heavily criticised for promoting. The process is akin to cleaning up or erasing uncomfortable historical content and the results are closer to the authoritative, curatorial, descriptive “neutrality” of traditional GLAM cataloguing than might be intended.

To elucidate our argument and observations, we start by offering a critical examination of the important work already carried out by the PMC, specifically its removal and replacement of a racist word in the titles of the photographic records for a painting by Bartholomew Dandridge, ca. 1725. We also consider the object description for the original painting in the Yale Center for British Art’s “Collections Online” database.

What do revisions in the name of decolonisation achieve?

A Young Girl with an Enslaved Servant and a Dog, ca. 1725,4 a painting by Bartholomew Dandridge, is held in the collection of the Yale Center for British Art. There are two digital records for two mounted reference images of this painting in the PMC photographic archive, Young Girl with Dogs and Black Attendant (PA-F06993-0057) and A Young Girl with an Enslaved Servant and a Dog (PA-F01160-0007). In the digital catalogue records for each archive reference image we learn that the title has been revised at least twice, although it is unclear from the record when, why and by whom.

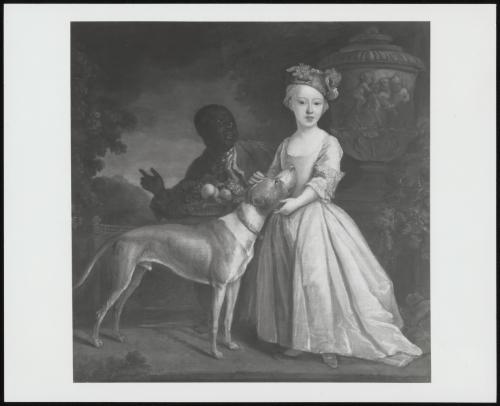

Fig. 1

Bartholomew Dandridge, A Young Girl with an Enslaved Servant and a Dog, ca. 1725. Paul Mellon Centre Photographic Archive (PA-F01160-0007).

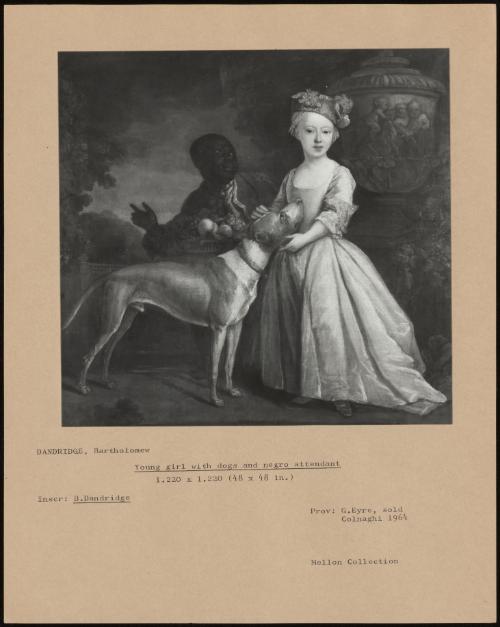

It is evident that previous revisions have attempted to address the language of the title. In the context of current moves to attend to problematic language within the GLAM sector, we can safely assume that “Young Girl with a Dog and a Negro Boy Attendant Holding a Basket of Fruit” was replaced by “A Young Girl with a Dog and a Page”, followed by “A Young Girl with an Enslaved Servant and a Dog”. For the record identifying the work as “Young Girl with Dogs and Black Attendant”, that version of the title was preceded by “Young Girl with Dogs and Negro Attendant”.

Fig. 2

Bartholomew Dandridge, Young Girl With Dogs And Black Attendant, ca. 1725. Paul Mellon Centre Photographic Archive (PA-F06993-0057).

Clearly, the offending term that has been addressed and can be seen in the “other titles” listed in the catalogue records is the word “Negro”—a term widely recognised as pejorative and racist in contemporary British and North-American contexts. The terms “Negro Boy Attendant” and “Page”, which gloss over the boy’s enslavement and are arguably as problematic because of their opacity, have most recently been replaced in the current title by the term “enslaved servant”. This offers a more honest and specific description of his societal role—as perceived by white audiences of the time—and of his relationship to the girl. However, this new term is not without its own problems. Despite the intention behind the change, its effect is to dehumanise the boy in the painting. The term “young girl” makes explicit her humanity, age and gender, whereas the dog is reduced to its species and the young boy—the “enslaved servant”—is reduced to his oppression, his social status (low) and his function (servile). Unlike the “young girl” he is not afforded a sense of individual personhood. Instead, he is identified according to his role or function in relation to the girl, rather than his own being. Thus, when the three elements within the new title are analysed comparatively, the term “enslaved servant” is arguably no improvement on “Negro boy attendant”, in terms of its acknowledgement of the boy’s humanity (something he was likely denied through his enslavement).5 “Black Attendant” serves no better, but provides a different set of concerns about racial identity, search retrievability, and historical accuracy.6

Fig. 3

Bartholomew Dandridge, A Young Girl with an Enslaved Servant and a Dog, ca. 1725. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection (B1981.25.205).

Just as changing an offensive word within the title of an artwork does not necessarily impact the problematic framing or representation of the people or histories being depicted, a revised title does not necessarily alter the problematic ways we read, think about, and describe the work represented in an object record or interpretive label. Descriptions of cultural objects and artworks produced by and within cultural institutions are highly selective and hierarchised presentations of knowledge about the object/artwork. The way the object/artwork is read, which information about it is selected, and the order in which it is presented arguably tells us more about the cultural and attitudinal contexts in which the description or interpretation is produced or encoded7 than it does about the object/artwork itself. Furthermore, even where revisions are being made with respect to racist language, an object description or interpretive label can still be a site where outdated, colonial, and racist thinking can be subtly, inadvertently reproduced, underscored, and perpetuated. To illustrate this point, we offer a critical annotation of an accompanying gallery label for Dandridge’s A Young Girl with an Enslaved Servant and a Dog written for the 2014 Yale Center for British Art exhibition, Figures of Empire: Slavery and Portraiture in Eighteenth-Century Atlantic Britain.8

Gallery label for Figures of Empire: Slavery and Portraiture in Eighteenth-Century Atlantic Britain

In a private garden, a young girl stands in a lace-trimmed dress, accompanied by a dog and an enslaved servant, who hands her a basket overflowing with peaches and freshly picked grapes. The servant and dog both wear metal collars that mark them as property. The dog’s collar is inscribed with what may be a name, possibly referring to the girl’s father; as a young woman, she could not own property.

In this portrait, Dandridge signals the girl’s virtues in several ways. The servant and dog gaze up at her, while she looks out at the viewer, establishing her central role and position of power in this scene. Dandridge’s painting gives especially clear expression to the way that many eighteenth-century portraits constructed their white sitters’ identities in relation to perceived “‘others,”’ including non-Europeans and animals. (A commonly held view in this period was that white Europeans occupied the highest point in a hierarchy of being in which black Africans ranked lower, and animals lower still.)

The relief on the urn, which shows a group of cherubs taming a wild goat—an allegory of carnal lust—serves as a contrast to the ostensibly chaste, “domesticated” love, which the young girl is shown to inspire in her two attendants. In fact, the possibility of sexual contact between white mistresses and black servants or slaves was a source of anxiety—and, as we will see in the next section, satirical comment—in this period.

Behind the Photographs—Imperial War Museums’ Case Study for the Provisional Semantics Project

One of the case studies in the Provisional Semantics project examined an Imperial War Museums’ (IWM) collection of photographs9 that were taken during the Second World War to document the recruitment of men into the British Indian army. In this case study, we encountered similar issues of representation, dehumanisation, and colonial narratives to those identified here. Since their arrival at the IWM, no descriptions or interpretation had been produced for this collection; curators and researchers were reliant on the original captions affixed to the back of each photograph in 1942. The premise of the case study, therefore, was to revise the captions for online publication and produce new interpretation material for the photographs, without replicating the problematic language found on the back. However, it quickly became apparent that avoiding the reproduction of colonial terms in new “descriptive” titles and interpretation texts was simply not enough. We had to carefully contend with how socio-political and historical contexts for the photographs were being described, taking into account questions of institutional and individual agendas and the intention of a variety of different actors, including the photographer, the person writing the original caption, and the person writing the new interpretation as part of the project case study.

In our assessment of the original captions, we found that it was not only the obviously pejorative words, such as “primitive”, that needed addressing, but also a range of more subtle descriptions and phrases. For example, the more lyrical contextual description, “The immemorial ox cart still holds sway in India, just as in Old Testament times”,10 is not as innocuous as it may first seem. In the context of these colonial propagandist photographs, the function of such descriptions was to promote the highly problematic and questionable notion that India was undergoing a process of modernisation at the hands of the British army in service of the civilising force of Empire. We therefore needed to be alert to the underlying context, purpose, and effect, not only of individual words but also of the longer descriptions that accompanied the photographs.

Despite the objectives of the project and case study, we also became aware that problematic or loaded concepts and phrases, such as “the bread basket of India”11 and “martial races”12 were being uncritically incorporated as neutrally descriptive terms in early versions of the new interpretation. Occasionally too, the casual and persistent habit of describing and identifying the Indian men pictured in the photographs by the colour of their skin (despite the photographs being black and white) surfaced in the process of writing the new descriptions, effectively othering, objectifying and racialising the men depicted once again. That these kinds of phrases, ideas and habits are so easily repeated and published without sufficiently problematising them is evidence of the thoroughly embedded structural racism in prevalent narrations and understandings of history. One of our key findings was that, in order to be able to identify why such terms require critical assessment and to therefore be able to avoid reproducing them unthinkingly in new interpretation, it is crucial to engage with a combination of stakeholder and source community knowledge, as well as subject-specialist and specific socio-political and historical research.

Conclusion

When conducting these critical analyses of object titles, descriptions, and interpretations, it is imperative that we acknowledge the process of emotional dislocation that occurs when discussing the representation of human subjects, such as the boy in Dandridge’s painting and the men in the IWM photographs. The exercise of analysis, without further research, potentially diminishes their lives and experiences to representational cyphers in narratives beyond their control in reproductions, records, and related texts, of which this article is now one. In a 2020 essay titled “The Crying Child”, Temi Odumosu expertly draws together many of the concerns and complexities we have come across in our own research, and eloquently addresses “the unresolved ethical matters present in retrospective attempts to visualize colonialism”.13 Odumosu describes how the “European use and commodification of the enslaved body for manual labor transferred to the domain of the visual, producing a surplus of images in different materials (ink, paint, paper, silver, wood, porcelain) that became surrogates for unsanctioned intimacies”. This is manifestly played out in Dandridge’s painting and the IWM photographs, and revising the titles and texts does little (or indeed nothing) to change this situation. It is only through focused research that histories and contexts of colonial violence and imperial subjugation can begin to be genuinely addressed with both transparency and sensitivity.14

While we undeniably need to edit, update, and amend titles and texts that we understand as offensive, such changes do not alter the subject matter of the object or artwork, nor the artistic intention. Put simply, changing individual words is not a legitimate change in and of itself because it does not remove the inherent racism. We need to critically examine the nuances of the language we use and the way we build narratives and hierarchies within a single text and across multiple texts. Moreover, this work should be understood as partial and limited as only one among several strategies that should be undertaken concurrently, including biographic and contextual research, formal object analysis, stakeholder or source community interpretation, and contemporary artistic response, to name just a few. What these complementary approaches have in common is that they attempt to acknowledge and incorporate subjectivity into the process of description and interpretation, regarding both the subjectivity of people depicted and the subjective, interpretative nature of description.

To acknowledge, as we have done, the complex issues that arise when attempting to address racism in historical object titles and descriptions is not in any way to deny the experience of harm or offence they cause. Racist pejoratives should not be the first information a viewer encounters and preferred terms should be recognised and respected. Our intention is simply to highlight that wholesale, uncritical adoption of performative decolonial revisionism risks replicating the same colonial logics of control, pseudo-objectivity, and cultural authority that GLAM institutions have long been guilty of.

Footnotes

- Stuart Hall describes this process of encoding in broadcast media in ways that seem usefully applicable to the production, publication (or broadcast) of object information in: Stuart Hall, “Encoding and Decoding in the Television Discourse [originally 1973; republished 2007]”, in Essential Essays, Volume 1, New York: Duke University Press, 2020, 257–276.↩︎

- There are relatively few UK specific resources that directly address cataloguing in the GLAM sector. Many of the most cited derive from research done by and with the source or indigenous communities of America, Canada, Australia, and Aotearoa New Zealand and primarily address what are described as ethnographic collections. Material culture referred to as “fine art” is much less well served, and the specifics of racism and British colonial history in catalogue records is not systematically addressed. One of the most significant publications, and one that addresses many of the same concerns we discuss here is National Museums for World Cultures, Words Matter: An Unfinished Guide to Word Choices in the Cultural Sector, 2018. Very recent examples of UK specific initiatives are Pitt Rivers Museum, Labelling Matters, 2021, https://www.prm.ox.ac.uk/labelling-matters; Carissa Chew, Inclusive Terminology Glossary Guidance on Non-Discriminatory Language for Cultural Heritage Professionals, Histories of Colour, 2021 and Decolonising Through Critical Librarianship, 2021, Cataloguing and Classification, https://decolonisingthroughcriticallibrarianship.wordpress.com/cataloguing-and-classification/.↩︎

- Tate, 2020, Provisional Semantics: Addressing the challenges of representing multiple perspectives within an evolving digitised national collection—Project | Tate, https://www.tate.org.uk/about-us/projects/provisional-semantics.↩︎

- Collections.britishart.yale.edu, 2014, A Young Girl with an Enslaved Servant and a Dog—YCBA Collections Search, https://collections.britishart.yale.edu/catalog/tms:715.↩︎

- How would our engagement with, and understanding of the painting change if it were titled, for example, “Two Children and a Dog” or “A Dog, a Little Boy and a Little Girl” (identifying the figures from left to right and using contemporary, informal parlance that will be familiar to all English-speaking audiences)? Although it would underscore the humanity of the two children like “boy attendant” it would not acknowledge the power dynamics being depicted. Instead, the role and status of each figure could be acknowledged, for example, “A Pet Dog, an Enslaved Boy and an Aristocratic Girl”.↩︎

- There is of course, some difficulty in attributing the source or validity of titles, simply from the digital records, or even the mounted reference images. Without further research we cannot be certain from the online record whether the first title listed was originally allocated to the painting by the artist, whether this was done by subsequent owners or dealers or curators. It is likely the girl was in fact at some point identified by name, as in a comparative work by Dandridge represented in the Photographic Archive, “Miss Peckham of Little Green, Chichester” (PA-F06993-0073), though in that work the figure of the boy is not even deemed worthy of mention, reducing his presence to compositional device.↩︎

- Hall, “Encoding and Decoding in the Television Discourse”.↩︎

- Interactive.britishart.yale.edu, 2022. A Young Girl with an Enslaved Servant and a Dog, https://interactive.britishart.yale.edu/slavery-and-portraiture/269/a-young-girl-with-an-enslaved-servant-and-a-dog.↩︎

- Imperial War Museums, 2021, Provisional Semantics: Behind the Photographs, https://www.iwm.org.uk/research/research-projects/provisional-semantics/behind-the-photographs.↩︎

- Link to the record with the original and updated captions: https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205637248.↩︎

- Despite our focus, this phrase was published without a contextual explanation as to why it could be problematic. Essentially, it is a colonial construction that reduces the province of Punjab to its usefulness in the service of the Empire, when other areas of India were experiencing famine as result of imperial mismanagement.↩︎

- See the following links for information about the problematic nature of this term: https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205637237 and https://www.iwm.org.uk/research/research-projects/provisional-semantics/context.↩︎

- Temi Odumosu, “The Crying Child: On Colonial Archives, Digitization, and Ethics of Care in the Cultural Commons”, Current Anthropology, vol. 61, no. S22, 2020, pp. 289–302, DOI:10.1086/710062.↩︎

- In her work on the unnamed and supposedly unknown Black models of nineteenth-century French painting, Denise Murrell argues for a disruption of the traditional art historical hierarchy of subject and gaze, through meticulous research into the Black actors represented in fine art, which can restore both humanity and agency to the individuals represented. In Denise Murrell, Posing Modernity: The Black Model from Manet and Matisse to Today, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018. While re-inserting the biographies of unnamed Black figures has been presumed difficult to impossible, there have been an increasing number of recent examples that contradict this.↩︎