Case Study 4: John Hamilton Mortimer

Introduction

This essay sets out to contextualise the John Hamilton Mortimer images in the Paul Mellon Centre’s Photographic Archive by exploring the scholarship which prompted the creation and collection of the images. It also shows the relationship between these images and the additional resources held in the Centre’s archive collections and, in doing, so highlights the myriad ways in which the Centre fulfils its founding role: to support the study and research of British art.

Most significant among these additional resources are the research papers of perhaps the three most significant UK-based Mortimer scholars: Gilbert Benthall, Benedict Nicolson and John Sunderland. The story of how the Centre acquired these materials is a complex narrative in its own right, and one that reveals much about the study of art history in the UK during the twentieth century.

The Paul Mellon Foundation for British Art

In 1964, the newly established Paul Mellon Foundation (predecessor to the Centre) was approached by David Galer, curator at the Towner Art Gallery, Eastbourne, for support with a proposed exhibition on the artist John Hamilton Mortimer. His enquiry was warmly received by the Foundation, where it was felt that an overview of Mortimer’s work was long overdue. Despite Mortimer’s relative success in his lifetime, and his association with the better-known painter Johan Zoffany, he had fallen somewhat from the notice of art historians. In 1965, Basil Taylor (Director of the Foundation) wrote to Galer stating that “ever since the Foundation had been set up it has been my wish to include among our publications a study of Mortimer”. He proposed that Benedict Nicolson, editor of the Burlington Magazine, was the man for the job, being a “mature and practiced scholar and an equally experienced and competent writer, [who] has been working for many years on related artists of the mid-eighteenth century”.1

By 1967, work on the exhibition was well underway and the Foundation was playing a pivotal role. Files in the Centre’s Institutional Archive reveal that—although the total amount of the grant is undocumented—it bore the full cost of the catalogue being prepared by Benedict Nicolson, as well as the cost of the transportation of pictures from the United States. This was, in fact, the sixth such grant to be awarded by the Foundation, and it demonstrates how the institution encouraged and supported scholarship in the field of British art, not only by providing much needed financial assistance, but by identifying neglected areas of scholarship and the scholars who might conduct work in these areas.

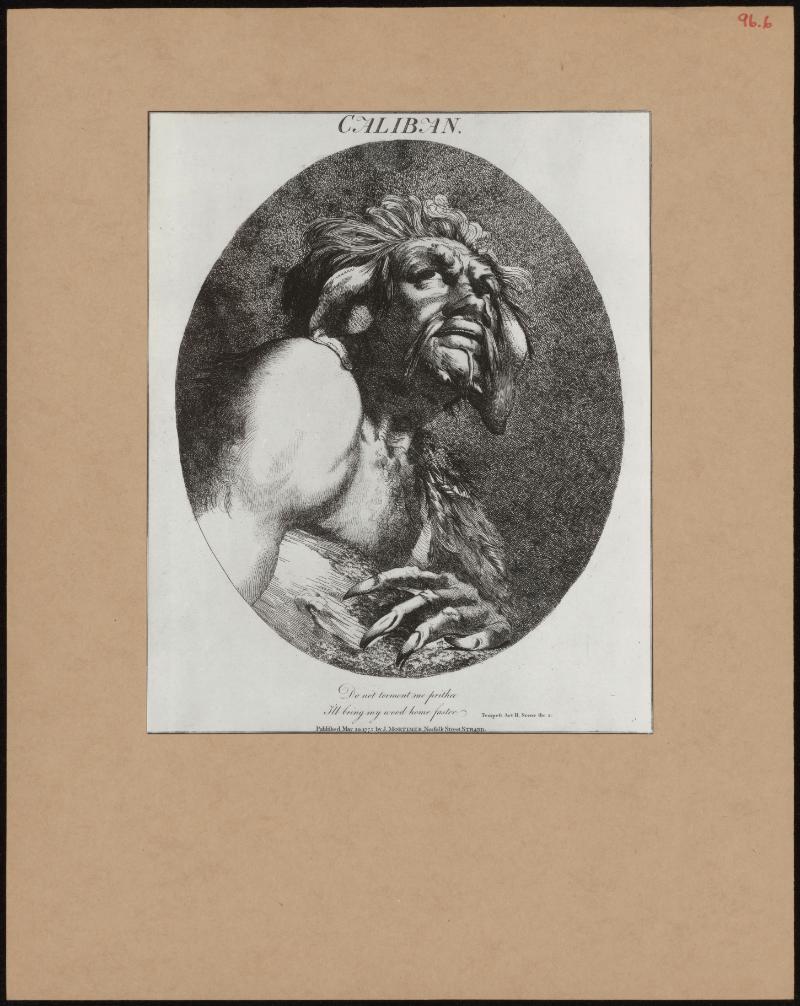

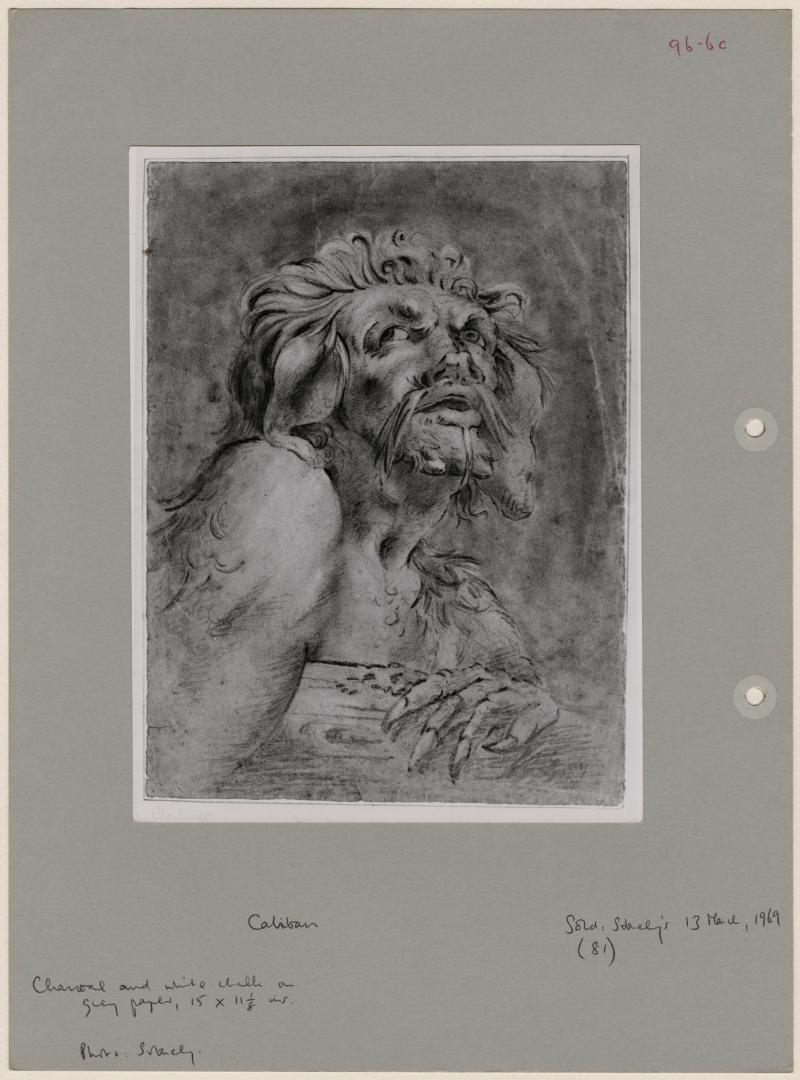

In addition, the Foundation also provided in-kind assistance for such ventures. It undertook a large part of the secretarial and administrative work involved in arranging the exhibition, and also organised the photography for the exhibition catalogue. Indeed, the files in the Institutional Archive reveal that Nicolson regularly sent out the Foundation’s photographer, Douglas Smith, to undertake the often challenging task of capturing Mortimer’s works on film.2 These photographs were used to illustrate the exhibition catalogue, and then added to the then embryonic, but rapidly growing, Photographic Archive.

Benedict Nicolson and Gilbert Benthall

In the course of Nicolson’s research on Mortimer, he became aware of a comprehensive catalogue of the artist’s works which was, as he describes, “reposing in the library” at the V&A.3 This had been compiled by the collector and amateur art historian, Gilbert Benthall (1880–1961). Alongside the catalogue itself, which took the form of a collection of loosely bound, hand-written sheets, were a selection of Benthall’s detailed notes on the artist, and a collection of images of Mortimer’s pictures. This was clearly the work of a diligent and enthusiastic researcher, but one which had never found published form.

Nicolson immediately understood how important this material would be to his own research. He tried to contact Benthall, but found out that he had died in 1961. It seemed, however, that Benthall’s widow was very helpful, and thrilled that her husband’s work was of interest to researchers. When he met her, Nicolson was pleased to learn that, while attempting to garner interest from publishers, Benthall had created multiple copies of his handwritten manuscripts.

At some point after this meeting, these extra copies—copies of all of the volumes held at the V&A as well as some extra items—came into Nicolson’s possession. These materials helped shape his work on the exhibition and the selection of material he was getting photographed—much of which would become part of the Centre’s growing photographic archive.

Upon successful completion of the exhibition and the published catalogue, Nicolson decided to move on to other projects. However, he already had in mind someone who might succeed him in his researches on the artist. This was a young art historian whose work he had already published in the Burlington Magazine, and who was already writing about Mortimer and his contemporaries: John Sunderland.

John Sunderland

John Sunderland was Witt librarian at the Courtauld Institute for over thirty years. After completing his PhD at the Institute in 1965 he took up the post the following year and remained as librarian until his retirement in 2002. Among other responsibilities, he was custodian of the Witt Photographic Archive and had been using this resource to research and write articles on various artists, including Mortimer.

On 19 December 1968, Nicolson paid Sunderland a visit at his family home and gave him all of the research papers he had collected while working on the 1968 Mortimer exhibition, including the Benthall papers.4 This marked the start of what would become an almost twenty-year project in which Sunderland would build on this research to produce the catalogue raisonné of Mortimer’s works. In 1969, just after Sunderland began working on this project in earnest, the Paul Mellon Foundation photographed fifty-five works by Mortimer and added them to their steadily growing photographic archive.5 The Paul Mellon Centre, which succeeded the Foundation in 1970, continued to support and encourage Sunderland’s research throughout the following decade.6

Following several attempts to secure publication via its partner Yale University Press, the Centre decided to take a step back and allow the Walpole Society to publish the volume. They still had a crucial role to play, however, not least through funding half the cost of the illustrations. As the Centre’s then director, Michael Kitson, wrote to the Advisory Council (who oversaw the allocation of grants) the money would ensure that the volume included “350 illustrations on 120 plates and [that] virtually all of Mortimer’s works will thus be reproduced”.7 The finished work—both a monograph and catalogue raisonné—was published as a volume of the Walpole Society Journal (Vol. LII) in 1988, and remains the most comprehensive publication on the artist.

It had become standard practice to rearrange images in the Paul Mellon Centre’s Photographic Archive following the publication of a significant catalogue. As such, the Mortimer images were duly reorganised according to the catalogue numbers they had been assigned in Sunderland’s text. This remains their arrangement to date. In the process of compiling the publication, Sunderland had also created his own photographic archive.8 This collection of photographs overlaps with the Centre’s collection, as might be expected, but it also represented a working reference collection, including doubtful or wrongly attributed works, comparisons and copies after Mortimer.

Sunderland remained the authority on Mortimer into his retirement, receiving and responding to many letters on the artist’s life and works. After he died in 2018, his widow donated Sunderland’s research papers—including those of Benthall and Nicolson—to the Paul Mellon Centre. Since its acquisition, the John Sunderland Archive has been fully catalogued, and can be explored online. In this process, Sunderland’s papers have joined those of Ben Nicolson, Gilbert Benthall and many other art historians, critics, museum directors and curators, all of which make up the Centre’s rich archival collections.

Footnotes

- Letter from Basil Taylor to David Galer, dated 17 December 1965, PMC Institutional Archive, PMC/26/1/6.↩︎

- See Letter from Nicolson to Angus Stirling, dated 1 September 1967, PMC Institutional Archive, PMC34/8 (file 1 of 5), requesting photography of a stained glass window at Brasenose College.↩︎

- B. Nicolson, Towner Art Gallery and Iveagh Bequest, Kenwood (1968), John Hamilton Mortimer, 1740–1779: Paintings, Drawings and Prints (exhibition catalogue) London: Paul Mellon Foundation for British Art, p. 55.↩︎

- Letter from Sunderland to Nicolson, dated 20 December 1968, John Sunderland Archive, JNS/1/2/3.↩︎

- PMC Negatives ledger, 1969, PMC Institutional Archive, PMC62/3.↩︎

- See Letters between Sunderland and the Paul Mellon Centre, dated between 18 December 1969 and 8 August 1977 from the file titled, “Mortimer Publication: Correspondence”, John Sunderland Archive, JNS/1/11/1.↩︎

- Addendum to the Memorandum of Decisions, dated 10 November 1986, PMC Institutional Archive, PMC27/34.↩︎

- See Files titled, “Catalogue Entries Photographs”, John Sunderland Archive, JNS/1/11/14–33.↩︎